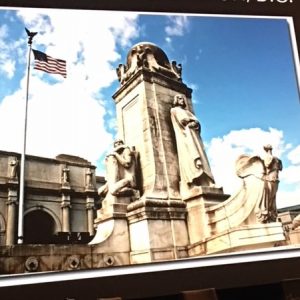

Columbus dominates this memorial, with Native American seated at left. Union Station, Washington DC. Photo by Kevin Gover

Racist images pervade our public spaces and mental landscape

If you missed the live feed of the symposium, Mascots, Myths, Memorials, and Memory on Saturday, March 3, you can still find the agenda on the program’s Facebook page, and a number of recordings of the talks on YouTube. There is also a great summary of the day by Allison Keys for Smithsonian Magazine. Held at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American Culture and History, the program was co-sponsored by the National Museum of the American Indian. The day featured historians, artists, and activists speaking about the racist images, both two and three-dimensional, that pervade our public spaces and our mental landscape. Viewpoints on the ultimate fate of these monuments varied. But there was general agreement on the psychological harm, especially to African American and Native American children, perpetrated by the unquestioned presence of these images in our midst. In a powerful keynote, author and activist Dr. Ibram X. Kendi recalled his encounters with the Confederate memorials and racist sports mascots of his youth in Manassas, VA. He likened them to unloaded guns, not lethal but delivering a threatening and powerful impact nonetheless. And he stressed that this was the effect intended by their creators.

What role can museums play?

As I listened to the discussion I realized that there could have been a fifth “M” in Mascots, Myths, Memorials, and Memory title: Museums–a subtext for much of the day. What role should our nation’s museums play in the examination of racist monuments, memorials, and mascots on display in their communities? Here are some thoughts generated by the symposium:

- Museums can host programs that feature expert discussion and public dialogue, such as this one. Although this program focused on nation-wide issues, any museum could examine memorials in its local community, partnering with other museums, parks, preservation groups, and historical societies.

- The examination of public memorials need not be limited to Confederate monuments. Statues of Columbus, pioneer monuments, sports mascots–there are a variety of public displays in cities and towns all over the country that include racist images of people of color and Native Americans.

- History and art museums can provide both historical context and aesthetic analysis for local monuments.. Many public displays that glorify European conquest and white dominion originated during the same period–the late 19th and early 20th century. European immigrants fleeing poverty and oppression, the black veterans returning from World War I and demanding their due–all were met with a nationwide backlash exemplified by the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. This was also the era of Jim Crow. Museums have the resources and expertise to examine these complex historical and social phenomena.

- Museums can host bus or walking tours of local sites,serving as a kind of referee or conflict resolution facilitator in interrogating locally contentious memorials or mascots.

- Museum staff can serve on boards or commissions appointed to examine these sites. A number of speakers on March 3 had been invited by mayors or other public officials to provide expertise and advice on the disposition of controversial monuments. Not all of these consultants agreed in their recommendations; among them were calls for removal of all monuments to a local preserve, for the addition of markers and labels that would provide context in place, for removal to a museum collection.

As many readers know, I am a member of The Empathetic Museum group, We provide resources and leadership to develop institutional empathy in museums. In communities where the wounds from public racist imagery persist, museums can practice institutional empathy by offering their considerable resources toward tending and healing these injuries.

If you are reading this post by email and want to comment, please go to Museum Commons or send a tweet to me @gretchjenn. Thank you.

Really nice post, Gretchen. Some thoughts (influenced by some of my more recent readings in memory studies)

1) Especially during the 2015 discussion the refrain became “Send it to a museum” and it seems like every two or three years this comes up, that in streets and public spaces the monuments are out of context but perhaps if they are in a museum that can give us context. At the same time, museum people were piping up that we are not simply trash cans for uncomfortable histories that people would rather forget… but no discussion ever really emerged on under what cases museums SHOULD take torn-down statues, or discussion of how museums should display these monuments (for example, if a Confederate monument is out of context on a street corner, isn’t he just as out of place if he’s just simply in the rotunda of your museum?) So that could be a concrete takeaway for museums: start thinking and discussing the politics, ethics, responsibilities and practicalities of accessioning these types of statues into our collections.

2) The Philly Mural Arts Monument Lab project was a really great example of how discussions/programs/collections/contemporary art can intersect with the ideas around monuments. I am sad that it hasn’t gotten nearly the amount of press and focus in memory studies that I think something like this deserved. So maybe

3) Look internationally. One of my favorite things about the forum at NMAAHC is that it included an international speaker. US society is unique in many ways, but this conversation exists in other spaces, and we could learn a lot. We are not the first country that’s tore down or built new monuments, nor will we be the last. We can learn from eastern Europe, etc.

4) In examining monuments, a certain language/critique has emerged, and not just in academic circles. Some of the language in both academic and non-academic circles around monuments can be applied to museums, so it’s useful for us to read as we have time about monuments and connect to applications of our own work and our own self-evaluation.

Thanks, Ali, I’m sorry this is a late reply. Have not gotten to this blog page in awhile. G